Alright guys, we've made it through the prelude, and now we're into the good stuff. Accordingly, my posts will get longer and more speculative. We've been introduced to a number of potential themes in Preludes and Nocturnes, and now, in Doll's House, Gaiman's vision will start to crystallize. I'm going to try and identify patterns as they emerge, and speculate as to their future relevance, and I look forward to everyone chiming in!

GENDER

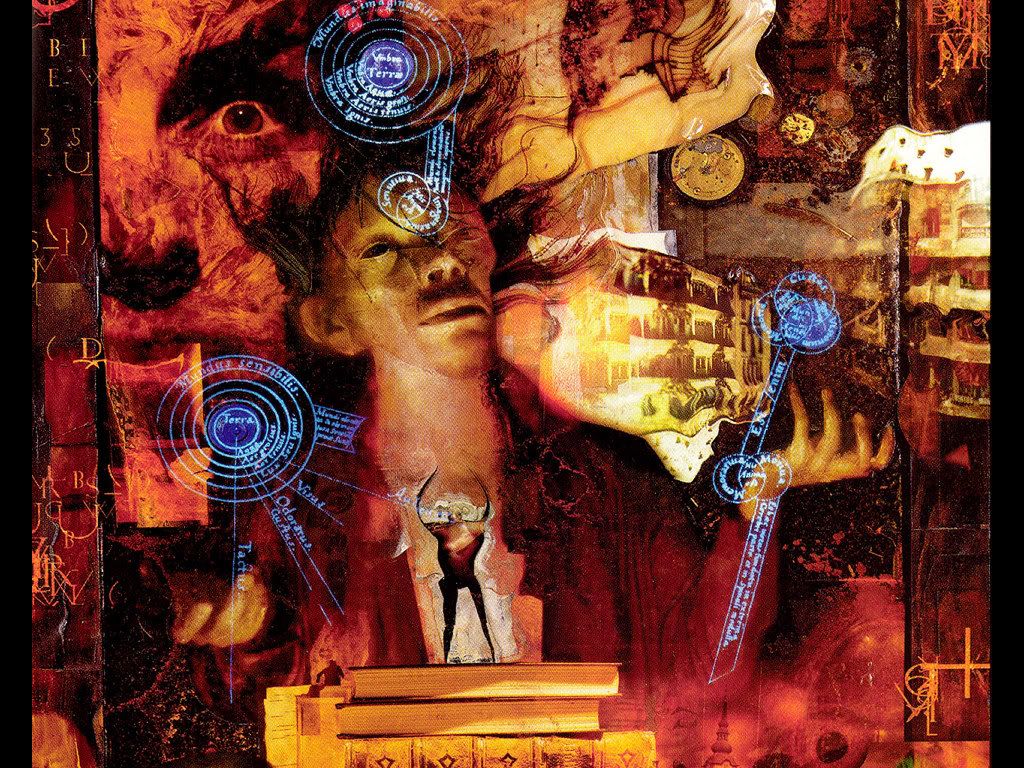

On the first page of the story, a giant phallus! Lest you think i ought to get my mind out of the gutter, the text supports the artistic rendering (or the art supports the text). Whatever. This equal weight between the art and the story was sorely lacking in Preludes and Nocturnes. If the story doesn't grip you, there's very rarely any artwork that distracts you from the words, no pretty pictures to seduce you otherwise. Basically, from panel one of Doll's House, we know that's changed: the very colors seem more vivid, more carefully selected. You can follow the story through the artwork, which I think is one of the most magical aspects of the comic medium.

But back to gender business. It's intriguing that the final step to manhood is not some show of force, no glamorous display, no taking of a female, but rather the simple hearing of a story. I suppose that's true in certain religions: in Hinduism and Judaism, where you have rites of passage for young people, what are the chants but stories, myths of morality, fables of warning?

Tales in the Sand is the first story in the Sandman mythology (or indeed any fiction I've read in some time) that recognizes how storytelling can be falsified by the simple fact of being a different gender. This is something that comes up often in feminist analysis of literature (most recently with Jonathan Franzen's Freedom, where an entire third of the novel is written from a female voice, but no one believes that it's anyone other than Franzen speaking).

I don't entirely buy into the idea that men can't write female stories, or vice versa, but Gaiman calls attention to the fact that there will be a subtle difference if a woman told this story, which is certainly true. Then again, I believe there would be subtle differences if anyone else told the story, period. This is the power of the storyteller; we can manipulate reality to our own advantage (and we hope not to receive the horrible fate of the poor waitress in the diner, who also tried to manipulate reality to her advantage).

I haven't really discussed it as yet, but gender has been an integral part of the story so far: for the most part, the villains have been male and the victims have been female. Also, all the females in the story have exercised what would certainly have been considered abnormal or even deviant sexuality at the time (the 1980's!). Think of "24 Hours." You could almost read it as a morality play: each woman in the story is an adulterer, a lesbian, or a necrophiliac. But Gaiman's aims are never so prosaic; he fails as a writer when he comes off as preachy, as preaching seems so opposite to what he's trying to achieve in this grand series.

This is what is known as overthinking.

DESIGNING THE ENDLESS

I don't know if it's a design issue or what, but the glass object that the old man requests closely resembles the materioptikon. Oh Dream, totally unable to keep ahold of his powerful talismans (that's what she said).

There's also an interesting suggestion that the mortal relationship with the Endless is one of our own making; the boy refers to "Grandmother Death," and Nada obviously has a sexual relationship with Dream (or Kai'ckul in this case). We do have some control over them: they appear in manners designed to appease our own aesthetic sense (and it's hard to remember today, given Neil Gaiman's mainstream success, but Sandman was a hot goth property in its early years).

Also, and most excitingly, look at the Dreaming through Nada's eyes! It's not fun and frolic, it's bloody terrifying! Cain and Abel's constant fighting is not just a repeated amusement, but to her it's a serious battle. And notice how she makes the first reference to the "Endless," that it is 'not given to mortals to love the endless.'

CITIES WITHIN CITIES

Cities and space also hold great importance within the mythology: I don't know if it's Neil Gaiman's ability to bring his settings to life, or whether there will be a greater significance to the whole concept of domain. Domains are clearly defined both emotionally and spacially; different characters fight for sovereignty over everything from emotion to territory. This is true of all humanity, I suppose, but this emphasis lends to the idea that there's a larger game at play. Larger than mortals, larger than the Endless. So I'm gonna start keeping track of city references: obviously we already have the Dreaming, and Hell, and Earth. But now we have the legend of the City of Glass (I wonder if this is an intentional Paul Auster reference, another writer who challenges the notion of story at its base).

Not to mention the king of the birds, an earthbound god who still rules his domain in the sky from his home in the 'hot lands of the North.'

ON POISONED APPLES AND OTHER SUCH THINGS

Gaiman doesn't bother too much with Biblical myths, which is but one of the reasons I enjoy his work so much (I do sincerely feel that sometimes atheists are bitter that they are not as able to craft stories as compelling as those in the Bible, and I get irritated when an author's entire oeuvre is dedicated to refuting those myths without coming up with his/her own new stories, new fables, etc).

But there is a weaverbird, who tempts Nada with berries, and my mind goes straight to Persephone and not to Eve, whether that was Gaiman's intention or not. But of course he's creating a myth of his own, of why the weaverbird is now brown and free from attack.

But then, there's another myth that comes up: in this story, Dream is Zeus, and Nada is Europa, who tries to escape the god by transforming into an animal, only to fail.

Everyone who knows me knows that I hate origin stories. But I am incredibly amused by the concept of origin stories for origin stories.

Coming up: And thusly we meet the family. Two families, for that matter.

Ha! Good catch with the phallic objects. Of course two men on a long trek might well be carrying spears, but the symbolism is rather...pointed.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, I am a dolt. I must have read this story a dozen times and I swear I just noticed the significance of the desert. All that sand. Oh dear.

Incidentally, those glass shards remind me more of Desire's sigil than Dream's ruby (the materioptikon was Dee's ruby-powered device for controlling dreams). They also remind me that life sometimes imitates art.

While we're logging themes and motifs, surely the major one here is the tale within a tale (within a tale, within a tale). More than anything else, Sandman is a story about stories.

As you say, it's significant that in this culture manhood is not achieved by doing, but by learning. You're not a man until you've heard the tale - or at least one version of it. Another lesson to take from this issue: stories vary with the storyteller. They are lies that tell us true things. You have to wonder what the women tell each other that the men do not, since Morpheus comes off very badly even in this version. Some of the contributors to the Sandman Annotations seem sure that in the female telling, Morpheus rapes Nada. Me, I look at the desert and I see something...barren. Perhaps in another version she did become his queen, but could never give him a child ("I still love you...but I have not yet forgiven you").

I don't know if it's true to say that mortals control the Endless. We view them through the prism of our own culture; same light, different sunglasses.

As to the flavour of the story, Gaiman's said that he wrote it as an original piece after a lot of reading in African mythology. Even so, the weaverbird makes me think of Kipling more than anything else. Is there a connection between Persephone and berries?

Dammit you've caught up to my posting! Now that my posts are getting exponentially longer, it's going to be hard to keep it up more than a couple times a week (but absence makes the heart grow fonder? right?)

ReplyDeleteI think what you mention is the great thing about this story: it doesn't leave you wanting more, as such, but it does leave you wanting to hear the other side. Such a magical idea, especially in this era where we can pick and choose opinionated commentary to the exclusion of all others.