While I generally enjoyed Maud Newton's increasingly controversial piece on David Foster Wallace, there was something that rubbed me the wrong way, and I've been trying to figure out exactly what that is, until I worked out that it is, in fact, almost everything about the piece.

Edward Champion, in an absolutely superb rebuttal, accuses Newton of a lack of intellectual seriousness, of failing to do the research that shows that David Foster Wallace cannot be blamed for the so-called folksiness permeating the web. (I don't think you even have to do research to prove this, but hey, the New York Times can't openly publish an article lambasting all writing styles that aren't their own, and so they have to somehow make it relate to their books commentary).

WHAT'S UP WITH ALL THIS TALKIN' LIKE REAL PEOPLE, Y'ALL?

Newton writes that:

Never before had “folks” been used so relentlessly and enthusiastically as a term of general address outside church suppers, chain restaurants and family reunions.

Um, really? I'm from Texas, and Newton has her own Texas roots, and I can guaran-damn-tee it that I heard "folks" absolutely everywhere. It's what urban/suburban Texans say instead of "y'all." It's how the politicians speak. But let's ignore her selective memory. I'm more troubled by the notion that folksiness is inherently a bad thing.

I think this snobbery comes partly from University insistence that the only good way to write is like Ernest Hemingway, clear, concise, free of embellishment. But would anyone accuse Flannery O'Connor of being unserious? How about William Faulkner? Mark Twain? Or Martin Luther King, Jr.? Or David Foster Wallace, for that matter? He may be many things to many people, but even when he's funny, he's intellectually rigorous.

Newton seems to conflate unserious language with Southern dialectical norms, which is all the more surprising given how many times she's blogged about the liveliness of Southern Texan vernacular.

But I guess that doesn't bother me too much. If I had a penny for every time I heard someone act snobbish about Southern or Midwestern turns of phrase I'd be swimming in copper.

WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT INTERNET COMMUNICATION

What troubles me more is how she defines the nature of blogging and internet communication, how she ignores its many and varied uses and the exciting transmutations of language within.

I suppose it made sense, when blogging was new, that there was some confusion about voice. Was a blog more like writing or more like speech? Soon it became a contrived and shambling hybrid of the two. The “sort ofs” and “reallys” and “ums” and “you knows” that we use in conversation were codified as the central connectors in the blogger lexicon. We weren’t just mad, we were sort of enraged; no one was merely confused, but kind of totally mystified. That music blog we liked was really pretty much the only one that, um, you know, got it.

I remember when blogging was new. You know who blogged? People who wanted to share information, but weren't able to do so through available media channels. Teenagers. Mothers. Would-be writers. Political agitators. Sports Fans. Pornographers. Every variety of geek. These groups are unified ONLY in that they are now able to express themselves to large audiences without conforming to any demands of "style." These are not people that communicate in the real-life sphere, so the idea that there was some "confusion about voice" is patently ridiculous. Was there someone attempting to develop a "style guide" for the internet? Absolutely not. The magic of the internet is its freedom from such shackles.

Early bloggers knew this, and the immense variety of writing styles reflected this. Does Salon resemble Slate resemble Gawker resemble Drudge Report? Of course not.

THE MUSIC BLOG EXAMPLE

Let's just look at the music blog example she uses (out of nowhere, and without any relevance to the story at hand). First of all, she seems not to comment on the writing within the blog, but how we react to it, which has nothing to do with her central point. Secondly, has she ever read a music blog? Let's look at Pitchfork, one of the greatest internet success stories.

First paragraph of original review of Funeral, by The Arcade Fire:

Ours is a generation overwhelmed by frustration, unrest, dread, and tragedy. Fear is wholly pervasive in American society, but we manage nonetheless to build our defenses in subtle ways-- we scoff at arbitrary, color-coded "threat" levels; we receive our information from comedians and laugh at politicians. Upon the turn of the 21st century, we have come to know our isolation well. Our self-imposed solitude renders us politically and spiritually inert, but rather than take steps to heal our emotional and existential wounds, we have chosen to revel in them. We consume the affected martyrdom of our purported idols and spit it back in mocking defiance. We forget that "emo" was once derived from emotion, and that in our buying and selling of personal pain, or the cynical approximation of it, we feel nothing.

Wordy and pretentious it certainly is, but there's not a single "um," "sort of," or "kind of," in the mix.

This, on Radiohead's Kid A:

"The experience and emotions tied to listening to Kid A are like witnessing the stillborn birth of a child while simultaneously having the opportunity to see her play in the afterlife on Imax."

Still no sort ofs or ums, and yet it's a completely different style! Variety in style! Imagine that!

And just for fun, go read comedian David Cross's spoof of the Pitchfork style. Still not a single 'sort of' or 'um'.

IN CONCLUSION, SORT OF

Newton concludes that:

Qualifications are necessary sometimes. Anticipating and defusing opposing arguments has been a vital rhetorical strategy since at least the days of Aristotle. Satire and ridicule, when done well, are high art. But the idea is to provoke and persuade, not to soothe. And the best way to make an argument is to make it, straightforwardly, honestly, passionately, without regard to whether people will like you afterward.

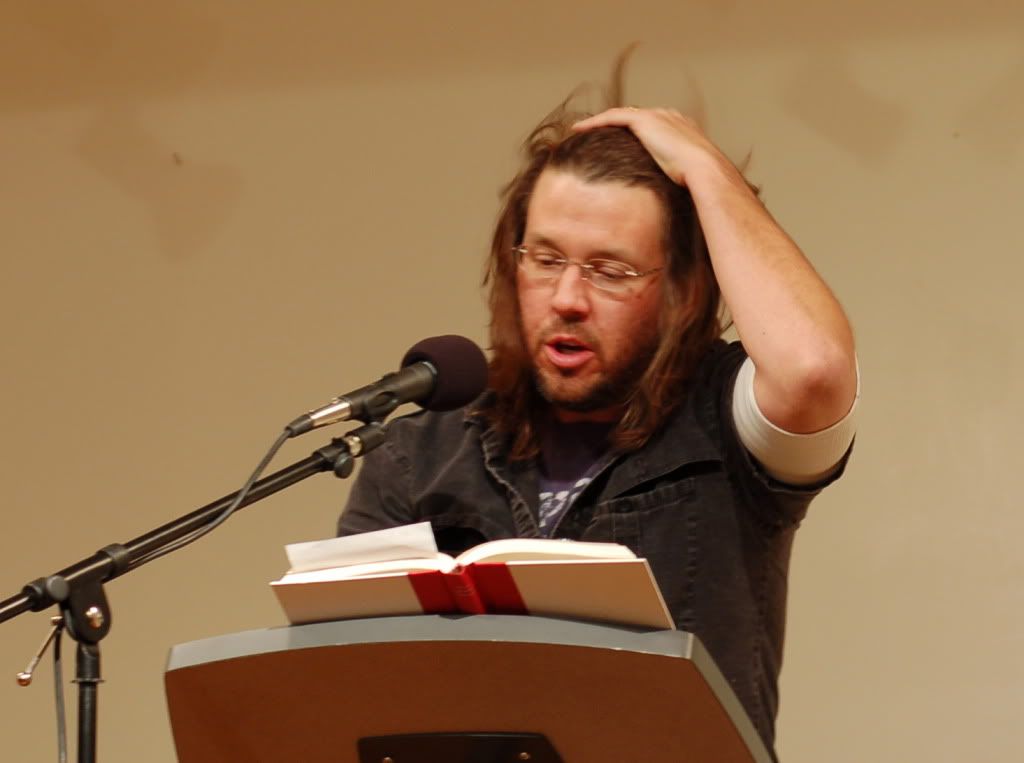

When she refers to soothing, does she describe DFW or the blogosphere? Neither would be described as "soothing" by any reader. I would argue that nowhere has her closing sentence been more ably accomplished than in the wild west of the World Wide Web. The problem with her article is that she offers little or no evidence to support her conclusions, apart from the aforementioned oblique reference to "music blogs". In many ways, I resent most that the target is David Foster Wallace, who isn't even alive to defend himself against these poorly delineated charges.

I have been harsh on Maud Newton, who writes a blog that I genuinely enjoy. It's possible that the failures of this article may be more generally attributable to the New York Times's general need to stand up for the status quo (for the internet revolution will eventually render them bankrupt). There are a large number of players in what I would describe as the "monetized paper" industry that are invested in protecting their superiority, in preserving their position as standard-bearers. It's sad when the only way to do that is to denigrate evolution in language and in style. And in this case, the article explicitly condemns certain trends without providing any examples to support that those trends even exist.